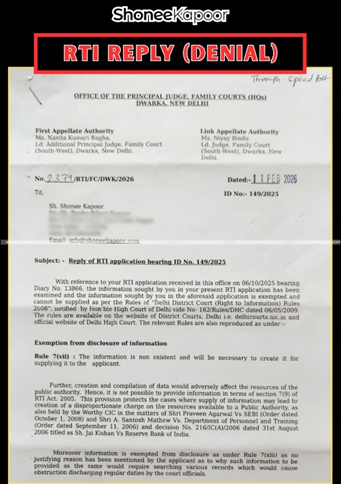

Family Courts have refused to provide year-wise divorce and alimony statistics under the RTI Act, citing technical grounds. Legal experts say the rejection contradicts the RTI Act, 2005 and binding Supreme Court precedents on judicial transparency.

NEW DELHI: India speaks endlessly about transparency.

But when hard data is sought about divorce litigation, Family Courts suddenly say:

- “Information does not exist.”

- “It would require creation.”

- “Disproportionate diversion of resources.”

- “No justification provided.”

This is not just administrative laziness.

It is a direct violation of the Right to Information Act, 2005 — and Supreme Court precedents.

And it raises a larger question:

Why is statistical transparency resisted when it concerns matrimonial litigation affecting men?

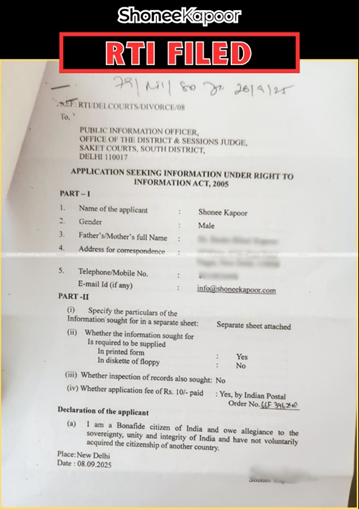

What Was Asked?

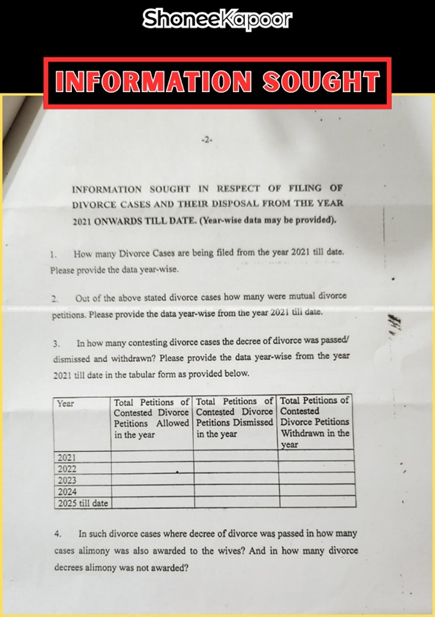

An RTI application sought aggregate, year-wise data (2021 onwards):

- Total divorce cases filed

- Mutual consent divorce petitions

- Contested divorce outcomes (allowed / dismissed / withdrawn)

- In decreed cases, how many involved alimony awards

No personal data.

No case files.

No confidential proceedings.

Only anonymized statistical information.

Section 6(2) RTI Act: No Reason Required

The rejection cited lack of “justification” for seeking information.

This is legally indefensible.

Section 6(2) of the RTI Act clearly states:

An applicant shall not be required to give any reason for requesting the information.

Public authorities cannot ask why a citizen seeks information.

This is black-letter law.

Section 7(9) RTI Act: Cannot Be Used to Deny Information

Authorities claimed “disproportionate diversion of resources.”

Section 7(9) does NOT allow refusal of information.

It only permits supplying information in a different form if the requested format is burdensome.

The Supreme Court in CBSE v. Aditya Bandopadhyay (2011) 8 SCC 497 held:

Information available in material form must be supplied unless exempt.

Statistical data maintained in electronic records is not “creation.”

Extraction is not compilation of fresh research.

If courts can upload pendency data to the National Judicial Data Grid (NJDG), they cannot claim statistical data does not exist.

Judiciary is a Public Authority Under RTI

In CPIO, Supreme Court of India v. Subhash Chandra Agarwal (2019) 16 SCC 1, a Constitution Bench held:

- The judiciary is a public authority under RTI.

- Transparency enhances accountability.

- Disclosure of non-sensitive information strengthens public trust.

Aggregate divorce statistics:

- Do not invade privacy

- Do not concern fiduciary relationships

- Do not attract Section 8 exemptions

Therefore, they are disclosable.

Section 4: Proactive Disclosure is Mandatory

The Supreme Court in Kishan Chand Jain v. Union of India (2023 SCC OnLine SC 915) emphasized:

- Public authorities must proactively disclose operational information.

- Section 4 compliance must be monitored.

- Transparency reduces the need for RTI applications.

Divorce filings and disposal statistics fall squarely within administrative functioning.

If pendency data is proactively disclosed, outcome statistics cannot be selectively withheld.

Selective transparency is not transparency.

Why Divorce Data Matters — Especially for Men

Public debate around matrimonial law is narrative-driven.

But data matters.

Questions that require empirical answers:

- What percentage of contested divorce petitions are dismissed?

- How many cases are withdrawn?

- What proportion of decrees involve alimony awards?

- What is the actual ratio of mutual consent vs contested divorces?

In India, men routinely face:

- Section 498A IPC (now Section 85, Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023)

- Domestic Violence Act proceedings

- Maintenance under Section 125 CrPC (now Section 144 BNSS, 2023)

- Interim maintenance under Section 24 Hindu Marriage Act

- Permanent alimony under Section 25 Hindu Marriage Act

The Supreme Court in Rajnesh v. Neha (2020) 9 SCC 1 laid down structured maintenance guidelines because of widespread inconsistencies and misuse.

When laws carry serious financial and criminal consequences, transparency in outcomes becomes essential.

Without data:

- Public perception is shaped by anecdote.

- Policy debates lack evidence.

- Men facing litigation operate in informational darkness.

Transparency is not anti-women.

It is pro-rule of law.

“Information Non-Existent” — An Administrative Improbability

Family Courts operate on:

- Case Information System (CIS)

- Digitized filing categories

- Disposal classifications

- NJDG reporting

Cases are categorized at filing and at disposal.

To say aggregate data “does not exist” is administratively implausible.

The RTI Act does not require creation of new information.

But it absolutely mandates disclosure of information that exists in electronic or physical records.

The Larger Question

Why is it that:

- Judicial pendency statistics are proudly displayed,

- But outcome statistics in matrimonial litigation are resisted?

Transparency should not stop where uncomfortable questions begin.

If dismissal rates are high, the public has a right to know.

If alimony awards are rare, the public has a right to know.

If mutual consent dominates, the public has a right to know.

Democracy functions on informed debate — not selective disclosure.

The Legal Position is Clear

The rejection violates:

- Section 6(2), RTI Act, 2005

- Section 2(f), definition of information

- Section 7(9), improper invocation

- Section 4, proactive disclosure obligations

- Supreme Court rulings in:

- CBSE v. Aditya Bandopadhyay (2011)

- Subhash Chandra Agarwal (2019)

- Kishan Chand Jain (2023)

- Rajnesh v. Neha (2020)

This is not activism.

This is statutory enforcement.

What Happens Next

Appeals will follow.

If required, the matter will be escalated to ensure:

Judicial statistical data cannot be insulated from public scrutiny.

Men facing matrimonial litigation deserve transparency.

Citizens deserve transparency.

The RTI Act is not ornamental legislation.

It is enforceable law.

And transparency cannot be selective.

FAQ’s

No. Under Section 6(2) of the RTI Act, no reason is required to seek information, and Section 7(9) cannot be used to deny existing statistical data.

Yes. Section 2(f) defines information to include records and data held in any form, including aggregate judicial statistics.

Yes. In CPIO v. Subhash Chandra Agarwal (2019), the Supreme Court held that the judiciary is a public authority under the RTI Act.

Such data reveals trends in contested cases, dismissals, withdrawals, and maintenance awards, helping ensure informed debate and accountability in matrimonial law.

The applicant can file a First Appeal under Section 19(1) of the RTI Act and, if necessary, escalate to the Information Commission for enforcement.

Leave A Comment