The Rajasthan High Court has set aside a POCSO conviction, holding that the prosecution failed to prove the victim’s minority and the allegations beyond a reasonable doubt.

The Court warned that criminal law cannot be driven by assumptions, suspicion, or selective evidence.

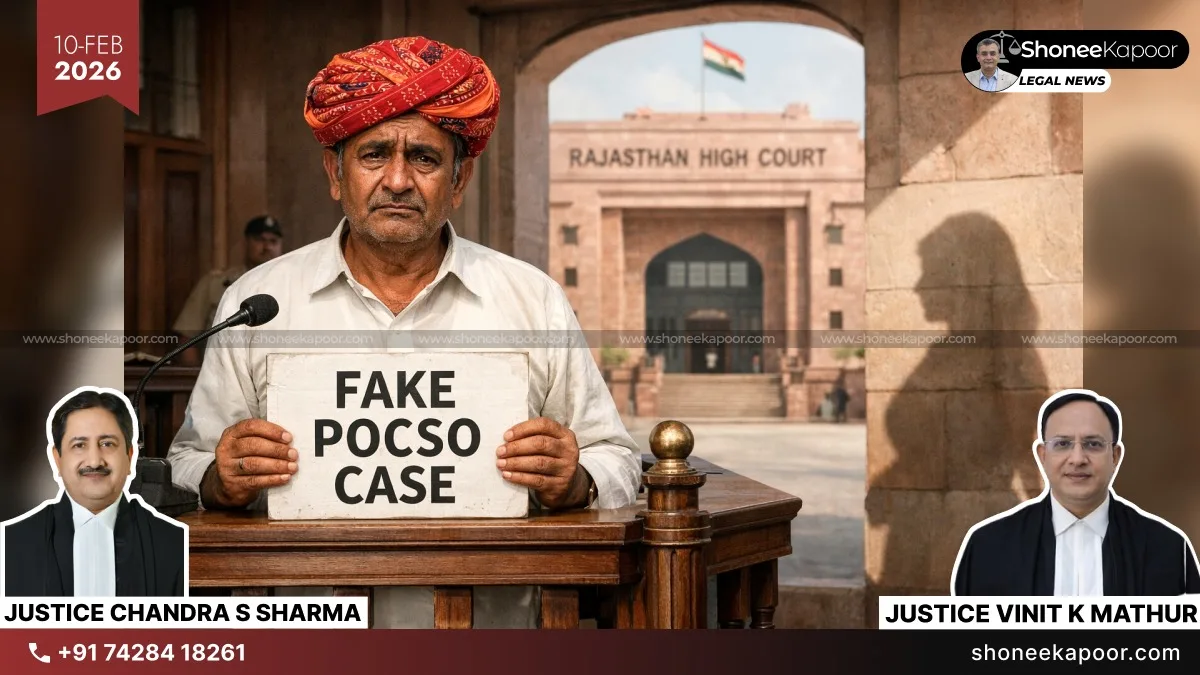

JAIPUR: The Rajasthan High Court has acquitted a former sarpanch who was earlier convicted under the POCSO – Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act. The Court found the prosecution’s version doubtful on multiple counts and held that the conduct attributed to the prosecutrix did not align with ordinary human behaviour.

The division bench comprising Justice Vinit Kumar Mathur and Justice Chandra Shekhar Sharma was hearing an appeal filed by the accused challenging his conviction in a case relating to the alleged sexual assault of a 17-year-old girl.

According to the prosecution, the girl had travelled with the appellant for passport-related formalities. It was alleged that during a night journey in a sleeper bus, the appellant committed sexual assault, which was said to have continued after they reached a hotel.

After examining the record, the High Court found serious inconsistencies and gaps in the prosecution’s story—a major issue before the Court was the age of the prosecutrix. The prosecution relied on a Secondary Board marksheet to show that she was a minor. However, government records indicated that she was a major.

The Court observed that while a school certificate can be relevant, when there are contradictions in official records, the earliest admission record carries greater evidentiary value. In this context, the Court noted that suppression of the best available evidence regarding age justified drawing an adverse inference against the prosecution.

Applying settled principles of criminal law, the bench reiterated that when two views are possible, the one favourable to the accused must prevail. On this basis, the Court concluded that the prosecution had failed to establish the minority of the victim beyond a reasonable doubt.

The Court also considered the about 24-hour delay in lodging the FIR. While acknowledging that delay alone is not always fatal in sexual offence cases, the Court clearly held that delay assumes significance when combined with other doubtful circumstances.

It observed:

“While delay in reporting a sexual offence is not per se fatal, an unexplained delay coupled with contradictions and surrounding suspicious circumstances affects the credibility of the prosecution case”.

Another factor that weighed heavily with the Court was a new assertion made by the prosecutrix during the proceedings, claiming that she had been subjected to sexual intercourse by the appellant on an earlier occasion as well. This allegation was not mentioned in her initial statements.

On this aspect, the Court reasoned that it was highly improbable that a girl would voluntarily travel again with a person who had earlier raped her. The Court also found it difficult to accept that, despite an alleged rape in a sleeper bus, the prosecutrix continued to accompany the appellant to a hotel, even though she had opportunities in a public setting to raise an alarm or seek help.

In strong words, the Court stated:

“The conduct attributed to the prosecutrix, viewed in the aforesaid factual matrix, appears wholly unnatural and inconsistent with ordinary human behaviour.”

Summing up the evidence as a whole, the bench recorded:

“When the evidence is appreciated cumulatively, it becomes evident that the prosecution case is riddled with inconsistencies, omissions, and investigative deficiencies…The minority of the prosecutrix is not conclusively established; the foundational story is improbable; the delay in FIR is unexplained; the earliest version is withheld; independent corroborative evidence is absent; and the medical evidence does not support the prosecution narrative.”

The High Court further underlined that a criminal conviction cannot be based on suspicion, emotions, or conjecture. It emphasised that proof beyond a reasonable doubt is not a formality or slogan, but a constitutional safeguard meant to protect personal liberty from wrongful deprivation.

In this background, the appeal was allowed, and the conviction of the former sarpanch under the POCSO Act was set aside. The judgment serves as a reminder that even in sensitive cases, the rule of law demands fairness, consistency, and strict adherence to evidentiary standards, ensuring that innocent individuals are not punished based on doubtful narratives or incomplete investigations.

Explanatory Table: Laws & Sections Involved In The Case

| Law / Statute | Section | What the Section Deals With | Conviction set aside due to failure to prove allegations beyond a reasonable doubt |

| Indian Penal Code, 1860 | Section 376(2)(n) | Punishment for repeated rape | Not proved as the minority itself was not established |

| Indian Penal Code, 1860 | Section 376(2)(f) | Rape of a minor girl | Enhanced punishment when an offence is committed on the grounds of caste |

| Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012 | Section 5(L) | Aggravated penetrative sexual assault | Automatically collapsed once the minority was not proved |

| Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012 | Section 6 | Punishment for aggravated penetrative sexual assault | Failed because the age of the prosecutrix was not proved conclusively |

| Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 | Section 3(2)(v) | Set aside along with the main conviction | Examination of the accused |

| Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 | Section 374(2) | Appeal against conviction | Appeal allowed |

| Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 | Section 313 | Enhanced punishment when an offence committed on the grounds of caste | Bond to appear before the Supreme Court if required |

| Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 | Section 437A | The accused denied the allegations and claimed false implication | Bond of ₹50,000 directed after acquittal |

| Indian Penal Code, 1860 | Section 228A | Followed by the Court | Victim anonymised as “prosecutrix” |

| POCSO Act, 2012 | Section 23 | Confidentiality of victim identity | Followed by Court |

- CASE TITLE: Lajendra Singh @ Lali vs State of Rajasthan

- BENCH: Hon’ble Mr Justice Vinit Kumar M. Mathur & Hon’ble Mr. Justice Chandra Shekhar Sharma

- NEUTRAL CITATION: 2026:RJ-JD:5728-DB

- COURT DETAILS

- Court: High Court of Judicature for Rajasthan

- Bench Location: JoDBr

- Case Type: D.B. DBiminal Appeal (DB)

- Appeal Number: 187/2020

- Appellant

- Name: Lajendra Singh @ Lali

- Father’s Name: Shri Boga Singh

- Age: About 30 years

- Address: Basant Vihar, Police Station Sadar, Sri Ganganagar, Rajasthan

- Status at Time of Appeal: On bail (sentence suspended earlier)

- Respondent

- State of Rajasthan

- Through: Public Prosecutor

Counsels Appeared

- For the Appellant

- Mr Vineet Jain, Senior Advocate

- Assisted by Mr. Praveen Vyas

- For the State: Mr. Rajesh Bhati, Public Prosecutor

- For the Complainant

- Mr. N.L. Joshi

- Ms. Kirti Pareek

Key Takeaways

- False implication thrives where investigation is lazy

Withholding the first school record, ignoring CCTV, and skipping independent witnesses shows how weak investigations can destroy an innocent man’s life. - POCSO is not an automatic conviction law

Prosecution must prove the minority beyond a doubt; assumptions and selective documents are not evidence. - Delay + contradictions matter in men’s defence.

Unexplained FIR delay, changed versions, and missing first disclosure seriously weaken credibility. - Human conduct test protects innocent men.

Courts will question narratives that defy normal human behaviour instead of blindly accepting allegations. - Liberty over optics

Criminal law exists to protect liberty, not to satisfy public pressure or emotional prosecution.

This Could Change Your Case-Get FREE Legal Advice-Click Here!

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the Indian courts and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of “ShoneeKapoor.com” or its affiliates. This article is intended for informational and educational purposes only. The content provided is not legal advice, and viewers should not act upon this information without seeking professional counsel. Viewer discretion is advised.