If two people decide to die together and only one survives, can the survivor escape legal punishment? The Supreme Court has now given a clear answer that reshapes how suicide pacts are treated under Indian law.

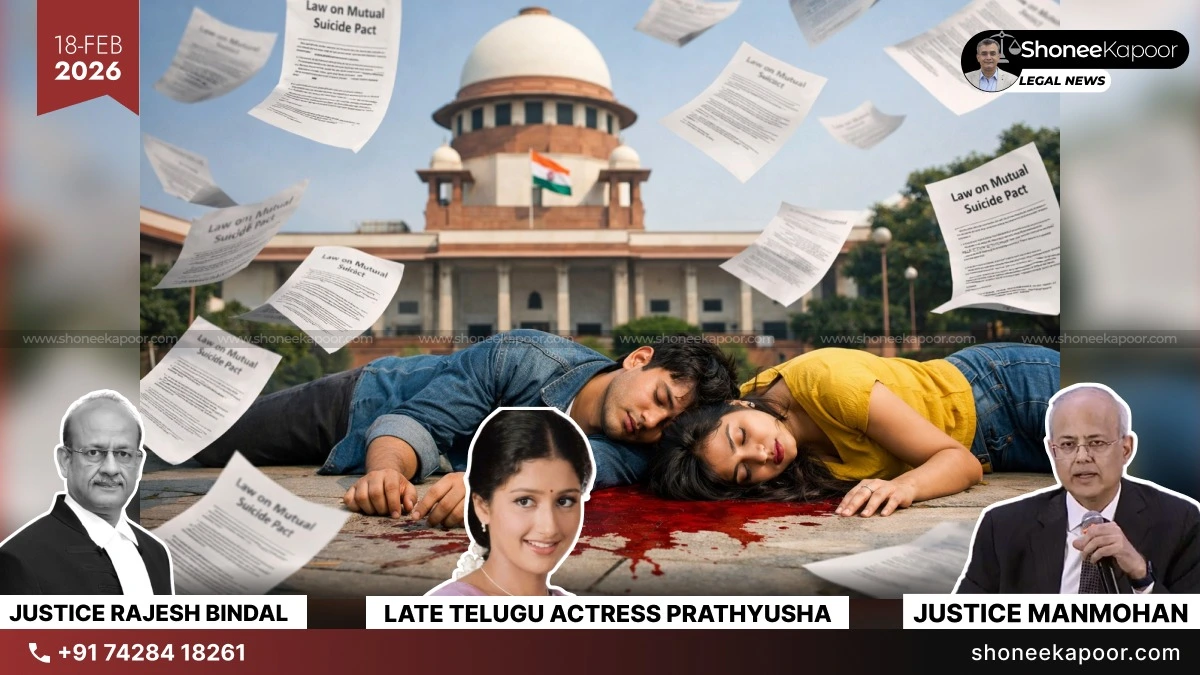

Actress Prathyusha Suicide: The Supreme Court of India clarified the legal consequences of a suicide pact. In the long-pending case related to the 2002 death of Telugu actress Prathyusha, the Court upheld the conviction of her boyfriend, Gudipalli Siddhartha Reddy, holding him guilty of abetment of suicide under Section 306 of the Indian Penal Code.

The Court firmly declared, “Suicide by a pact is culpable,” making it clear that law does not treat such arrangements as private emotional decisions without criminal liability. If two individuals mutually agree to end their lives and one survives, the survivor cannot escape responsibility.

The case had remained in litigation for over two decades, with serious allegations at different stages including claims of strangulation and sexual assault. However, after examining medical, forensic and documentary evidence in detail, the Supreme Court concluded that the death was due to organophosphate poisoning and not murder.

The Bench examined whether the case was a suicide pact or whether the accused had independently driven the actress to suicide. The Court held that the evidence clearly established a mutual suicide pact between the deceased and the accused.

It explained the legal position in clear terms, observing:

“A suicide pact involves mutual encouragement and reciprocal commitment to die together. The survivor’s presence and participation acts as a direct catalyst for the deceased’s actions.”

In the present case, it was found that the accused had purchased a highly toxic pesticide knowing its lethal nature. Both the deceased and the accused consumed the poison. While she died, he survived. The Court held that his act of procuring the poison itself amounted to intentional aid.

The judgment records:

“In the present case, the appellant-accused has abetted the offence under Section 306 of the IPC by purchasing the pesticide with the knowledge of its lethal nature. Furthermore, in absence of any explanation by the accused as to why the deceased and the accused consumed poison would lead to an adverse inference that it was consumed with intent to commit suicide.”

Importantly, the Court clarified that abetment is not limited to physical force or coercion. Psychological support and mutual commitment can also amount to abetment when there is clear intent and active participation.

The Bench underlined this by stating:

“If not for the active participation of both the parties, the act would not occur.”

The Court further held that law treats such conduct seriously because the State has a fundamental interest in preserving life. Therefore, assisting in ending life is treated as a crime against the State.

On the issue of culpability, the Bench made its conclusion clear:

“His participation directly facilitated the deceased’s suicide… His culpability therefore stands established.”

During arguments, the defence claimed that since both had gone to the hospital, it showed there was no intention to die. However, the Court rejected this theory, observing that rushing to hospital is a natural human reaction in the face of death and does not erase prior criminal participation.

The Court also drew adverse inference from the accused’s failure to explain crucial facts under Section 313 of CrPC.

The Bench recorded:

“There was adverse inference against the accused.”

The prosecution had established that the accused purchased Nuvacron pesticide on the same evening, met the deceased at a beauty parlour, and both were later admitted to CARE Hospital after consuming poison. The forensic reports confirmed organophosphate poisoning. Independent expert committees rejected the initial postmortem theory of strangulation and sexual assault.

The ruling has far-reaching implications. It brings clarity to situations where emotional pressure, family opposition or relationship breakdown leads couples to take extreme steps. The judgment makes it clear that a suicide pact does not dilute criminal liability. If one person survives, he or she can be prosecuted for abetment of suicide.

After reviewing all material, the Supreme Court dismissed both appeals — one filed by the accused challenging conviction and another filed by the deceased’s mother seeking enhancement and alternate findings.

The conviction under Section 306 IPC was upheld, and the accused was directed to surrender within four weeks to serve the remaining sentence.

Explanatory Table: All Laws And Sections Discussed In The Case

| Section / Law | Title / Provision | Purpose in Law | How It Applied in This Case |

| Section 306 IPC | Abetment of Suicide | Punishes anyone who abets (instigates, aids, or encourages) suicide | Accused held guilty for aiding suicide by purchasing lethal pesticide and participating in suicide pact |

| Section 107 IPC | Definition of Abetment | Defines abetment as instigation, conspiracy, or intentional aiding | Court held suicide pact falls within intentional aiding and mutual instigation |

| Section 309 IPC | Attempt to Commit Suicide | Punishes attempt to commit suicide | Accused survived after consuming poison; conviction under 309 also considered |

| Section 302 IPC | Murder | Punishment for murder | Initially alleged; ultimately ruled out as death was due to poisoning, not strangulation |

| Section 174 CrPC | Police Inquest Proceedings | Procedure for investigating unnatural deaths | FIR initially registered under this section |

| Section 313 CrPC | Examination of Accused | Accused must explain incriminating circumstances | Court drew adverse inference due to complete denial by accused |

| Section 386(b) CrPC | Appellate Powers | Power of appellate court to alter conviction or order retrial | Discussed in context of whether murder charges should be revived |

| Section 106 Evidence Act | Burden of Proof for Special Knowledge | Facts within special knowledge must be explained by accused | Court held accused failed to explain purchase and consumption of poison |

| Section 114 Evidence Act | Presumptions by Court | Court may presume existence of certain facts | Applied while assessing conduct and surrounding circumstances |

| Section 32(1) Evidence Act | Dying Declaration | Statement by deceased regarding cause of death | Deceased told doctor she consumed pesticide |

| Section 8 & 9 Evidence Act | Conduct & Relevant Facts | Conduct before/after event is relevant | Defence relied on hospital visit; Court rejected accidental theory |

| Probation of Offenders Act, 1958 (Section 4) | Release on Probation | Allows release instead of sentence in certain cases | Held inapplicable as Section 306 carries up to 10 years punishment |

Case Details

- Case Title: Gudipalli Siddhartha Reddy v. State C.B.I. With connected matter: Criminal Appeal Nos. 894–895 of 2012

- Neutral Citation: 2026 INSC 160

- Court: Supreme Court of India

- Jurisdiction: Criminal Appellate Jurisdiction

- Criminal Appeal No.: 457 of 2012 (with connected appeals 894–895/2012)

- Date of Judgment: February 17, 2026

- Bench: Justice Manmohan & Justice Rajesh Bindal

- Appellant (Main Appeal): Gudipalli Siddhartha Reddy

- Respondent: State C.B.I.

- Appellant in Connected Appeal: Mother of the deceased

- Counsel for Appellant-Accused: Mr. S. Nagamuthu, Senior Advocate & Mr. L. Narasimha Reddy, Senior Advocate

- Counsel for Mother of Deceased: Mr. Gireesh Kumar

- Counsel for Respondent-CBI: Mr. Nachiketa Joshi, Senior Advocate

- Final Outcome: Appeals dismissed. Conviction under Section 306 IPC upheld. Accused directed to surrender within four weeks.

Key Takeaways

- Both the man and the woman jointly decided to commit suicide; this was not a one-sided act, nor was it proven to be coercion.

- False narratives of rape and murder circulated for years before being medically and legally demolished, causing irreversible damage to the man’s reputation.

- The only proven act was that both consumed poison together — the difference was that she died and he lived.

- The Court treated survival as criminal liability under abetment law, effectively punishing him for participating in a mutual suicide pact and failing at his own attempt.

- This case exposes a harsh legal reality: when tragedy strikes in a relationship, the surviving man can become the automatic accused, even when the decision to die was mutual.

This Could Change Your Case-Get FREE Legal Advice-Click Here!

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the Indian courts and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of “ShoneeKapoor.com” or its affiliates. This article is intended for informational and educational purposes only. The content provided is not legal advice, and viewers should not act upon this information without seeking professional counsel. Viewer discretion is advised.